ZOMBIE PREPPERS – Using zombies to teach science and medicine

With my colleague Greg Tinkler, I spent an afternoon last week at a local public library talking to kids about zombies:

With my colleague Greg Tinkler, I spent an afternoon last week at a local public library talking to kids about zombies:

The Zombie Apocalypse is coming. Will you be ready? University of Iowa epidemiologist Dr. Tara Smith will talk about how a zombie virus might spread and how you can prepare. Get a list of emergency supplies to go home and build your own zombie kit, just in case. Find out what to do when the zombies come from neuroscientist Dr. Greg Tinkler. As a last resort, if you can’t beat them, join them. Disguise yourself as a zombie and chow down on brrraaaaiiins, then go home and freak out your parents.

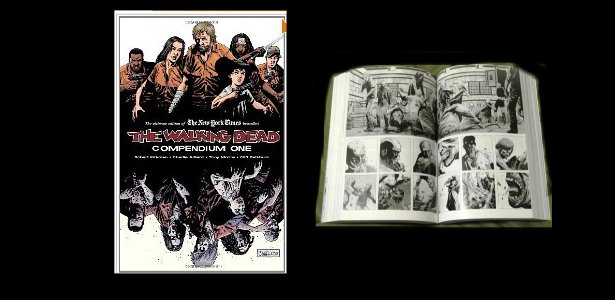

Why zombies? Obviously they’re a hot topic right now, particularly with the ascendance of The Walking Dead. They’re all over ComicCon. There are many different versions so the “rules” regarding zombies are flexible, and they can be used to teach all different kinds of scientific concepts–and more importantly, to teach kids how to *think* about translating some of this knowledge into practice (avoiding a zombie pandemic, surviving one, etc.) We ended up with about 30 people there: about 25 kids (using the term loosely, they ranged in age from maybe age 10 to 18 or so) and a smattering of adults. I covered the basics of disease transmission, then discussed how it applied to a potential “zombie germ,” while Greg explained how understanding the neurobiology of zombies can aid in fleeing from or killing them. The kids were involved, asked great questions, and even taught both of us a thing or two (and gave us additional zombie book recommendations!)

For infectious diseases, there are all kinds of literature-backed scenarios that can get kids discussing germs and epidemiology. People can die and reanimate as zombies, or they can just turn into infected “rage monsters” who try to eat you without actually dying first. They can have an extensive incubation period, or they can zombify almost immediately. Each situation calls for different types of responses–while the “living” zombies may be able to be killed in a number of different ways, for example, reanimated zombies typically can only be stopped by destroying the brains. Discussing these situations allows the kids to use critical thinking skills, to plan attacks and think through choice of weapons, escape routes and vehicles, and consider what they might need in a survival kit.

Likewise, zombie microbes can be spread through biting, through blood, through the air, by fomites or water, even by mosquitoes in some books. Agents can be viral, bacterial, fungal, prions or parasitic insect larvae (or combinations of those). Mulling on these different types of transmission issues and asking simple questions:

“How would you protect yourself if infection was spread through the air versus only spread by biting?”

“How well would isolation of infected people work if the incubation period is very long versus very short?”

“Why might you want to thoroughly wash your zombie-killing arrows before using them to kill squirrels, which you will then eat?” (ahem, Daryl)

can open up avenues of discussion into scientific issues that the kids don’t even realize they’re talking about (pandemic preparedness, for one). And the great thing is that these kids are *already experts* on the subject matter. They don’t have to learn about the epidemiology of a particular microbe to understand disease transmission and prevention, because they already know more than most of the adults do on the epidemiology of zombie diseases–the key is to get them to use that knowledge and broaden their thinking into various “what if” situations that they’re able to talk out and put pieces together.

It can be scary going to talk to kids. Since this was a new program, we didn’t know if anyone would even show up, or how it would go over. Greg brought a watermelon for some weapons demonstrations (household tools only–a screwdriver, hammer and a crowbar, no guns or Samurai swords) which was a big hit. Still, I realize many scientists are more comfortable talking with their peers than with 13-year-olds. Talking about something a bit ridiculous, like an impending zombie apocalypse, can lessen anxiety because it takes quite a lot of effort to be boring with that type of subject matter; it’s entertaining; and kids will listen. And after all, what you don’t know, might eat you.

10 Essentials for Surviving the Zombie Apocalypse: A Practical Guide

In many ways, vampires and zombies are two sides to the same coin. Both are undead. Both spread their condition through bites. Both have specific methods in which they can be killed. But vampires are the patricians of the undead with fussy European accents, bright sparkly skin, cheerleader girlfriends, tailored suits, and slinky party dresses. Zombies, on the other hand, are strictly blue-collar and, I daresay, typically American. They roam the streets, disheveled, dispossessed, homeless. They are the middle class, marginalized into oblivion.

Taken singly, zombies are slow, idiotic, and relatively easy to kill. Laughable, even, with their witless drive and ungainly movements. One zombie? Destroy the brain, drop the shambler. But collectively, zombies are an inexorable force, knocking down chain-link fences, busting through windows, treating your neighbors like bowls of spinach dip. They’re the ultimate union. And their collective bargaining powers can’t be legislated away.

To survive the zombie apocalypse, you’re going to need a plan. Survival means you’re going to have to accept the blue-collar ethos that the zombies embody. Time to roll up your sleeves, put on your best Mike Rowe face, and get ready to do some dirty work. In no particular order, here are 10 essential items for surviving the zombie apocalypse. For a more in depth exploration into zombie apocalypse survival techniques and items, feel free to check out This Dark Earth, my zombie survival treatise-cum-novel. Wait. Not a cum-novel. Strike that last bit. Sheesh, you people.

Headknockers come in a variety of shapes and sizes. You can find one in every garage, every toolbox in America. A hammer, a hatchet, a crowbar, a two-by-four. A Louisville slugger. Destroy the brain and you’re good to go. Big plus: relatively quiet and no need to reload.

Any more zombies than two, your best bet is hunching over in a protective ball, placing your head between your legs and giving your gluteus maximus one last smooch in thanks for all the good times.

If you have Kevlar motorcycle gear, in addition to looking cool, you’re freaking gold, hombre.

Unless you’re into the weird stuff.

ZOMBIE HISTORY – The Plague That Is Zombies

‘I hereby resolve to kill every vampire in America” writes the young Abraham Lincoln in the best-selling 2010 novel “Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.” Honest Abe doesn’t quite make good on his promise, and the grim results are all around us. Today, vampires spring from the shadows of our popular culture with deadening regularity, from the Anne Rice novels to the Twilight juggernaut to this year’s film adaptation about the ghoul-slaying Great Emancipator. Lately we’ve also endured a decadelong bout with the vampire’s undead cousin, the zombie, who has stalked films from “28 Days Later” to “Resident Evil” (the next sequel of which is due out this fall) and the popular TV show “The Walking Dead.”

‘I hereby resolve to kill every vampire in America” writes the young Abraham Lincoln in the best-selling 2010 novel “Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.” Honest Abe doesn’t quite make good on his promise, and the grim results are all around us. Today, vampires spring from the shadows of our popular culture with deadening regularity, from the Anne Rice novels to the Twilight juggernaut to this year’s film adaptation about the ghoul-slaying Great Emancipator. Lately we’ve also endured a decadelong bout with the vampire’s undead cousin, the zombie, who has stalked films from “28 Days Later” to “Resident Evil” (the next sequel of which is due out this fall) and the popular TV show “The Walking Dead.”

Purists will hold forth on the differences between vampire and zombie, but the family resemblance is unmistakable. Both are human forms seized by an animal aggression, which manifests itself in an insatiable desire to feed on the flesh of innocents. (Blood, brains, whatever; it’s a matter of taste.) Moreover, that very act of biting, in most contemporary versions of both myths, transforms the victims into undead ghouls themselves.

Our vampires and zombies (as well as such poor relations as werewolves) all serve as carriers for vaguely similar saliva-borne infections. These mythical contagions are especially odd because they have so few analogues in the natural world. Indeed, there is really only one: the rabies virus.

A fatal infection of the brain, rabies is particularly devastating to the limbic system, one of the most primitive parts of the brain. Fear, anger and desire are hijacked by the virus, which meanwhile replicates prolifically in the salivary glands. The infected host, deprived of any sense of caution, is driven to furious attack and sometimes also racked with intense sexual urges. Today we know that most new diseases come from our contact with animal populations, but with rabies this transition is visible, visceral, horrible. A maddened creature bites a human, and some time later, the human is seized with the same animal madness.

Known and feared for all of human history—references to it survive from Sumerian times—rabies has served for nearly as long as a literary metaphor. For the Greeks, the medical term for rabies (lyssa) also described an extreme sort of murderous hate, an insensate, animal rage that seizes Hector in “The Iliad” and, in Euripides’ tragedy of Heracles, goads the hero to slay his own family. The Oxford English Dictionary documents how the word “rabid” found similar purchase in English during the 17th century, as a term of illness but also as a wrenching state of agitation: “rabid with anguish” (1621), “rabid Griefe” (1646).

The roots of the vampire myth stretch back nearly as far. Tales of vampire-like creatures, formerly dead humans who return to suck the blood of the living, date to at least the Greeks, before rumors of their profusion in Eastern Europe drifted westward to capture the popular imagination during the 1700s.

In its original imagining, though, the premodern vampire differed from today’s in one crucial respect: His condition wasn’t contagious. Vampires were the dead, returned to life; they could kill and did so with abandon. But their nocturnal depredations seldom served to create more of themselves.

All that changed in mid-19th century England—at the very moment when contagion was first becoming understood and when public alarm about rabies was at its historical apex. Despite the fact that Britons were far more likely to die from murder (let alone cholera) than from rabies, tales of fatal cases filled the newspapers during the 1830s. This, too, was when the lurid sexual dimension of rabies infection came to the fore, as medical reports began to stress the hypersexual behavior of some end-stage rabies patients. Dubious veterinary thinkers spread a theory that dogs could acquire rabies spontaneously as a result of forced celibacy.

Thus did rabies embody the two dark themes—fatal disease and carnal abandon—that underlay the burgeoning tradition of English horror tales. Britain’s first popular vampire story was published in 1819 by John Polidori, formerly Lord Byron’s personal physician. The sensation it caused was due largely to the fact that its vampire, a self-involved, aristocratic Lothario, distinctly resembled the author’s erstwhile employer.

But Polidori’s Byronic ghoul only seduced and killed. It took until 1845, with the appearance of James Malcolm Rymer’s serialized horror story “Varney the Vampire,” for the vampire’s bite to become a properly rabid act of infection. For the first time readers were invited to linger on the vampire’s teeth, which protrude “like those of some wild animal, hideously, glaringly white, and fang-like.” And at the long tale’s end, Varney’s final victim (a girl named Clara) is herself transformed into a vampire and has to be destroyed in her grave with a stake.

Both these innovations carried over into the most important vampire tale of all, Bram Stoker’s “Dracula.” In Stoker’s hands, the vampire becomes a contagious, animalistic creature, and his condition is properly rabid. It is a lunge too far to claim (as one Spanish doctor has done in a published medical paper) that the vampire myth derived literally from rabies patients, misunderstood to be the walking dead. But it is clear that this central act of undead fiction—the bite, the infection, the transferred urge to bite again—has rabies knit into its DNA.

Over time, the vampire’s contagion infected his undead cousin, too. The original zombie myth, as it derived from Haitian lore, also involved the dead brought back to kill, but again without contagion—an absence that carried over to Hollywood’s earliest zombie flicks. In this and many other regards, the most influential zombie tale of the 20th century was nominally a vampire tale: Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel “I Am Legend,” whose marauding hordes of contagious “vampires,” victims of an apocalyptic infection, set the whole template for what we now think of as the standard zombie onslaught.

Since then, as Hollywood has felt the need to conjure ever more frightening cinematic menaces, the zombie has if anything grown increasingly rabid. The antagonists in Matheson’s novel can, at times, carry on an intelligent conversation with a normal human. By the 2007 film adaptation, starring Will Smith, the infected are howling, lunging, senselessly hateful animals inside a human form. Danny Boyle, the director of “28 Days Later,” has said outright that he modeled his zombie virus on rabies. But even if he hadn’t consciously done so, the name he gave that virus—”Rage”—already draws its power from the same centuries-old supply.

Westerners don’t have much cause to fear death from rabies these days. Thanks to the availability of vaccine, human fatalities in the U.S. have dropped to a handful per year; Britain got rid of the virus entirely in 1902, succeeding in just the sort of national eradication project that apparently stymied the vampire-slaying Abraham Lincoln. Yet the infected bite, the human turned animal aggressor, menaces us as often as ever on our flat screens and nightstands.

Rabies itself may be a distant concern, but the rabid idea, like Varney the vampire, still has teeth—and it still succeeds in spreading itself.